What do the Gastown riots, a woman in labour, and holding up burning buildings have in common? They make for great towing stories nearly fifty years later.

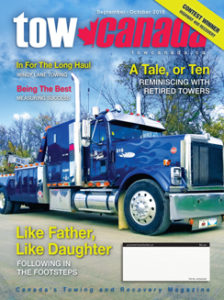

By Sarah Bruce

Illustrations by John Crossen

Vancouver, B.C. was a different place back in the 1970s. The city was a hub for miners and loggers returning home from camp. When they got home, a lot of them would take their paycheques right to the bars and spend the weekend living it up, sometimes leaving their cars parked illegally.

That is when the towers came in to do their job.

“Things were different back then, even in the late ’70s along the Granville strip. You had Hornby Street, Davie Street, Robson Street, and there were nightclubs on Georgia. Private impounds and even the bylaws were a constant [factor]. You were out until two or three in the morning, hauling cars out from all of these nightclubs,” said Charlie Brown, a now retired tower. He, along with Rowland Tucker and Rory Washtock, worked for Busters Auto Towing in that wilder era and they have the stories (and scars) to prove it.

“Unfortunately, back in that era, everybody hated tow truck drivers. Unless you were a woman who just happened to lock your baby in the car—then you were a hero. But other than that, they basically hated tow truck drivers because Busters was contracted by the city to clean the streets,” Charlie explained. “There were a lot more fights back then.”

Even though towers were just doing their job and following city bylaws, drunken, out-of-town workers did not appreciate this so much. “The nightlife downtown created a lot of havoc and it usually wasn’t the guy who owned the car, it was his drunk friend,” Rowland said.

“A lot of guys didn’t believe that you had the legal right to tow their car in those days,” Rory added. “They had come from Medicine Hat so they didn’t think you had any right at all, they’d come in fighting.”

“The Irish Rovers, from the Blarney Stone in Gastown, were some of Rory’s best opponents,” Charlie said, chuckling. “We had a battle royale in front of that place just for towing cars away. Something like that would never happen today.”

“Vancouver was boomtown,” Rowland explained. “All the miners and loggers would be in town. They’d been in camp for a month, so they’d come to town to party and do their thing. Take a bunch of drunken loggers and mix them with the miners and a bunch of truck drivers and there’s a fight.”

“They beat me up one time,” Rory said. “Cut the hell out of me. Skidded my face along the gravel.”

It was not even so much about the money. An impound back then set you back no more than $25 (approximately $150 in today’s money). But when a bunch of hot-tempered guys get together, and feel they have been wronged, there was often a confrontation.

“A guy comes in as I was just finishing up an auto club job,” Rory said, reflecting on a day at the impound lot. “He asks who towed his car, and Paul points to me and said, ‘He did it.’ I look over and the guy is straight up in the air above me. He was some judo expert. We fought him off and hit him with a piece of wood under the chin. He went to the hospital with his teeth hanging out of his face and I never saw him again. His wife put him in the back of the station wagon with the seat down and hauled him away.”

When they were not busy defending themselves, part of Busters’ legacy was assisting the police and fire departments. In fact, an editorial cartoonist for the

Vancouver Sun, Len Norris, often depicted Busters covering for the police, who just did not have the manpower or the patrol cars to always be the first responders. Instead, that fell to the towers.

“Back in that era, porto-power for fire trucks hadn’t been invented yet,” Charlie said. “When you were trapped in a car, it was the guy driving the tow truck that pulled the car apart, and then they’d go in and get the person out. All that fancy stuff they have today hadn’t been invented yet; it was still on the drawing board in somebody’s head.”

It helped that back then it was normal for towers to have police radios. They knew what was going on at the same time the other emergency departments did and could respond accordingly. With little competition in the industry, it was more about getting the job done than to whom the job went.

“I had a police radio in my truck when I started at Busters in ’71 and I could talk to the police dispatcher,” Charlie said. “You mention that today and they throw rocks at you. There wouldn’t be a way on God’s green Earth that would ever happen.”

The police even requested their help during the Gastown riots in the early ’70s. “We took the mirrors off the trucks,” Charlie explained. “We were told roads are to drive on, sidewalks are to walk on; you walk out in front of tow truck and guess what?” At least it got people out of the streets.

“Quite often at night in Vancouver we would get calls like, ‘There is something happening at Hastings and Boundary, will you go check it out?’” Charlie said. “Because they had few police cars, we would go out there and check it out and call our dispatcher to report whether it was an accident or a drunk fellow hitting his head.”

One night a fellow tower got sent out, Charlie recalled with a chuckle. “It was a woman in a payphone screaming but [the police department] had no one to go out and find out why. So Davy gets out to the payphone and then he gets back on the radio and all he could say was ‘I-I-I-I-I…’ Well, nobody told us, but she was in the process of having a baby. But he was in worse shape than she was. She was okay. If she could have got to the radio, she could have told you what the problem was but this wasn’t Davy’s cup of tea. It wasn’t a broken down car, he didn’t know what to do.” Someone else was eventually sent out to see what the problem was and took the woman to the hospital.

Of course, there were no guidelines, training manuals, or job descriptions back then. Towers did everything, from changing winches on the fish docks out in Steveston to helping out the fire department.

“When Gastown was on fire,” Charlie said, “I can remember taking one of the heavies in and running a cable through the wall of the building to the next wall to hold the wall up so it wouldn’t fall down on the fire trucks. Everything around me was on fire.”

Just as it is now, the industry was about solving problems. “You tell me what you need and we will see what we can do for you,” Charlie said. “They had a big train derailment down by New Brighton Park years ago, and I got sent down with one of the tandems. I told them, ‘Well, what the hell am I going to do with a tandem and a boxcar that weighs 300,000lbs.?’ To which they said, ‘Well, just go down and do something.’ So that’s what we did. We went down and did things until the railroad got their big tow truck in there.”

Thankfully, a lot has changed in the industry. Towers are still expected to take on nearly impossible tasks, but hopefully not involving a burning building or a woman in labour. Safety measures have improved, and public awareness is increasing, but even still, the industry has a long way to go.

All three towers reflected on how the greatest challenge in towing was that you were usually alone when faced with all these jobs.

“You had to do everything and you had to do it by yourself,” Rory said, reflecting on a recovery job he did at the top of the Sea-To-Sky Highway in his day. A Camaro crashed 500 feet off the road, which meant scaling an embankment 500 feet down, then back up to slacken the cable, then back down again to hook up, and back up to execute the recovery.

That has not changed. Towers still have to face difficult situations alone. Rowland thinks that if towers went to recoveries as a tandem team, the job would be considerably safer. If anything were to happen to a tower on the job, he or she could be left alone waiting, who knows how long, for help.

At least it was not all tough times. Rory recalled a memorable night that still leaves him chuckling nearly fifty years later.

“I got a call from Busters at 4:30 one summer morning to go to Wreck Beach [Vancouver’s notorious nude beach] and open a car,” Rory said. “There was a guy and a girl with no clothes on at all, and I said to the guy, ‘How in the hell did ya get someone to call you a tow truck?’ because they didn’t have cell phones back then, and all he said was, ‘With great difficulty.’”

The towing industry has changed drastically since the 70s, thanks to safety awareness and regulations, new innovations in towing equipment, and cellphones, but the one thing all have towers still have common is a good story, or ten.