by Curtis Hassell

Photos/illustrations courtesy Collins Manufacturing Corp.

Collins knows a thing or two about dollies. As inventor of the first self-loading dolly and leading dolly manufacturer for over 46 years, Collins has observed many dolly-training deficits.

Reading through the various towing forums, the uninitiated can draw multiple conclusions over a single event—often erroneously. Much of the disparity in operating the self-loading dolly stems from a lack of uniform

training or, for some, any real training at all.

We are here to help. Since first coming to the scene in 1972, self-loading dollies have been a mainstay for towing and recovery operations. From the design aspect of dolly development, Collins is pleased to offer Tow Canada readers with a seasoned perspective, for the purpose of dolly-safety education.

Pre-tow inspection: know before you tow

As pilots approach their aircraft, the first requirement is a pre-flight inspection of the airplane, to make sure it is airworthy and safe to operate. Professional tow operators should follow suit by conducting pre-tow

inspections of not only their trucks but also their equipment, such as dollies, to make sure they too are tow-worthy and safe to operate.

- Collins suggests checking the dollies for:

- Any physical damage that might compromise safety

- Fatigue cracking of material or welds

- Distortions of any components

- Freedom of movement of all components

- Smooth and quiet hub rotation—listen for possible worn or dry bearings

- Proper tire inflation

- Tire issues: bulges, cracking, weather checking, cuts, irregular tread wear, etc.

- Any loose or missing components, nuts, or bolts

- Safety tie-down straps should be free from defects or frayed webbing

By checking for hairline fatigue cracks before leaving the safe haven of the tow yard.

Complete failure can be avoided on the road, where fewer options are available.

Some of the largest consumers of aircraft-grade aluminum are, of course, aircraft manufacturers. And the airlines that purchase from them have a recommended lifecycle based on the number of landings before

retiring their fleet. It is no wonder therefore that aircraft-grade aluminum cross rails should be regarded the same way—especially given the sometimes-brute forces they are subjected to. Their lifecycle can also be quantified by keeping a logbook over time to determine when it is best to retire them.

Overstressing aluminum cross rails

Twenty years after the development of steel cambered telescopic cross rails in 1975, Collins introduced the first aluminum cambered telescopic cross rails in 1995. Because of their lightweight, their usage has skyrocketed to about 98 percent over steel.

A vehicle secured on aluminum cross rails may be within the dolly’s static load limits while sitting parked. But once the towing begins, the vehicle will commence vertical oscillation, thereby converting to a “dynamic” load. When a static load goes dynamic while towing, downward vertical forces can potentially overload the aluminum. Over time, hairline stress cracks may form, which if left unchecked, may result in unexpected structural failure.

Driving habits, road conditions, and vehicle weights should all be taken into consideration in prolonging the life of dolly equipment. The more aggressive the driving, the shorter the life cycle. Many operators

carry steel cross rails for heavier vehicles, and aluminum for all others.

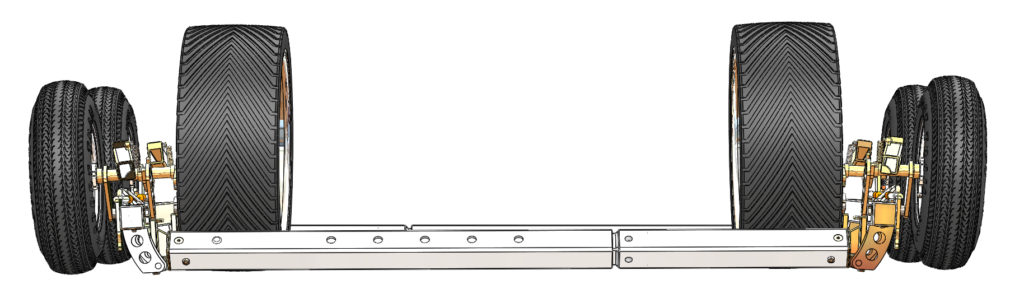

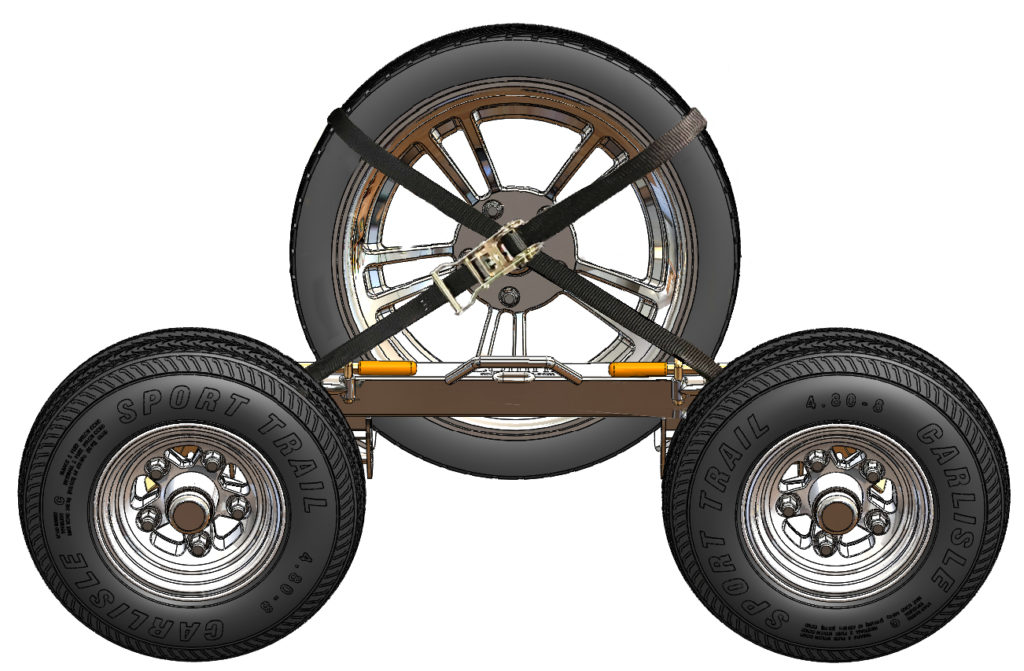

Setting up

Since other American dolly manufacturers, past and present, such as Tolle, Diversified, Granger, Magna Tech, and In The Ditch based their dolly/cross rail configurations on Collins’ original Tri-Pocket/Rail End design, the following applies universally: Telescopic cross rails should be adjusted so the ends are as close to the outside of vehicle’s tires as possible. This positions the vehicle’s weight closest to the dolly sides where strength is maximized, thereby decreasing the chance of hairline fatigue cracks, and increasing the life cycle of the aluminum.

Why safety ratchets?

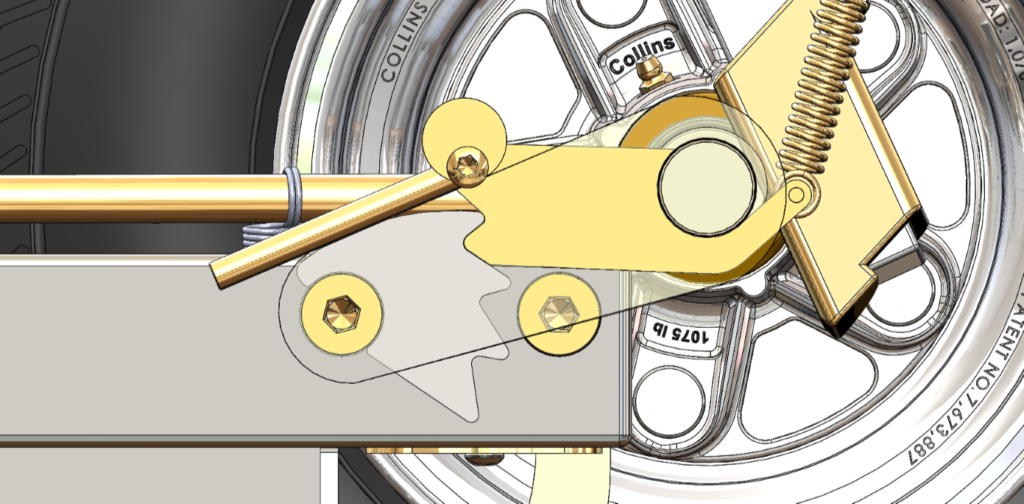

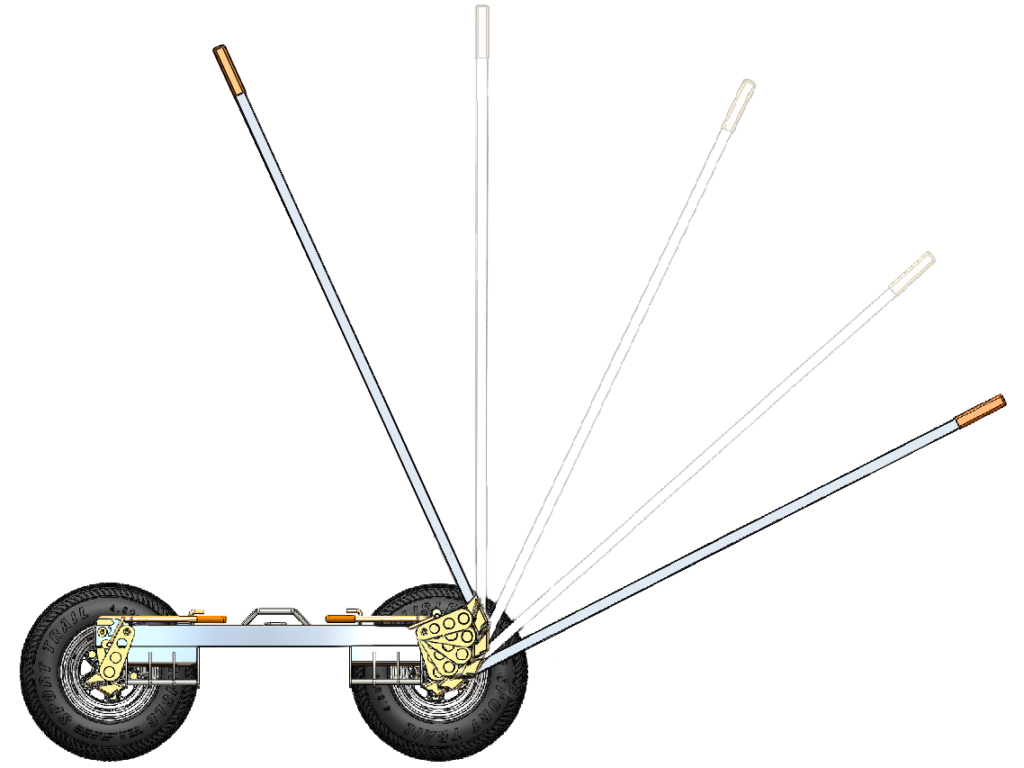

First, a little history: In the early years of the Collins Hi-Speed Dolly development, there were only four moving parts. Very simple, however, in 1977, tow operators expressed concern about the pry bar, (which leverages the dolly and vehicle off the ground), as a potential hazard.

They warned that the pry bar was inherently dangerous if tow operators ever slipped or lost their grip, potentially causing personal injury. Collins responded with the Safety Ratchet System, or SRS, which arrested

the free, unchecked motion of the pry bar.

This system also provided a safer option of stepping or ratcheting the vehicle up, off the ground. This was particularly useful for smaller-in-stature tow operators leveraging heavier vehicles, to be able to pause between pulls, to get better leverage.

The SRS also has a secondary role: backup safety. If the dolly ever inadvertently releases while in tow, the engaged safety ratchet prevents the dolly from dropping to the ground. Since 1977, the SRS has prevented countless injuries, accidents, and property damage.

Engaging safety ratchets prior to lifting the vehicle is the single most important step in safe dolly towing.

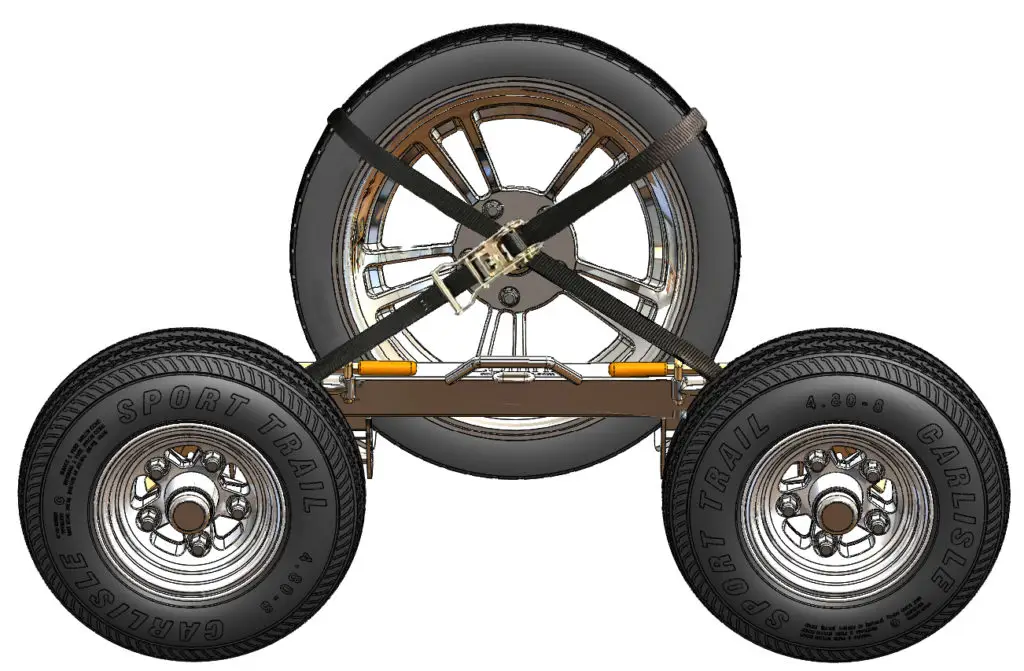

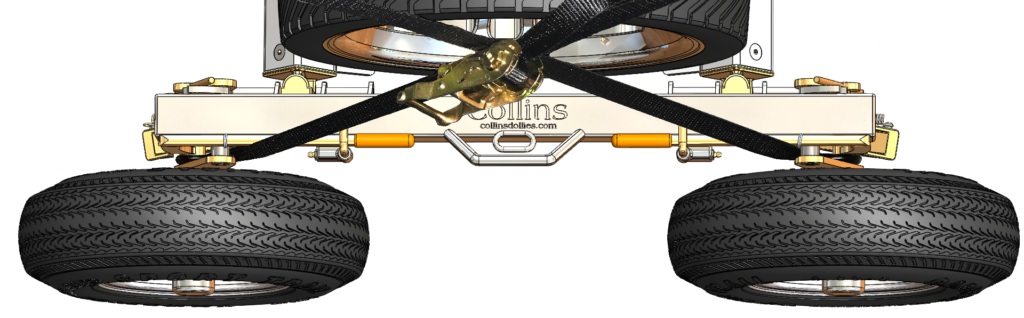

Lastly, various methods of securing vehicle tires to the dolly handle have been used. Collins however, recommends hooking safety tie-down straps directly to the dolly spindles. This method accomplishes two things:

1.) The complete dolly assembly and vehicle are secured together to act as a single unit.

2.) As additional safety, the spindle assemblies are prevented from accidentally unloading.

Step-by-step instructions for raising and lowering the self-loading dolly should be read carefully, and practiced empty, until the operator is completely familiar and comfortable with the process. They are available online for downloading and printing.

Safe and profitable towing!